The Planning Problem

(Updated August 2020)

The most important decision investors make in money management matters is dealing with the allocation of their assets between stocks and bonds. This decision determines the basic volatility/return characteristics of the portfolio and quantifies both the likelihood of realizing financial goals and the range of possible outcomes.

Many investors are overconcerned with the volatility of common stock returns and underconcerned with the damaging effects of inflation. To highlight these differences, the following model illustrates how investors can manage “return volatility” inherent in stocks, and “purchasing power risk” inherent in Treasury Bills, through a balanced asset allocation. Treasury Bills are used as a proxy for bonds and large company stocks are used as a proxy for equity investments. Treasury Bills have not produced the real returns necessary to preserve living standards over the long haul.

Historically, Treasury Bills have earned about 4% per year, while inflation has been about 3% per year, giving treasury bills a positive real return of about 1% per year. That’s assuming, of course, you don’t pay taxes. If you pay taxes probably your returns from treasuries are closer to zero or even negative. On the other hand, stocks have had real returns of around 6% per year. That would allow for much greater spending than available from investing in Treasury Bills. Of course, buying stocks requires taking investment risk. Therein lays the planning problem. On the one hand we need significant real returns to finance our retirement and maintain our standard of living, but we can’t do that without taking any risk.

The chart in the following table shows annualized real returns from 1927 to 2010 for six different portfolio combinations ranging from 100% stocks to 100% Treasury Bills. A riskier portfolio holds 100% stocks and the least volatile portfolio holds 100% bonds. Between these extremes lie standard stock-bond allocations such as 20-80, 40-60, 60-40 and 80-20. The index used for stocks is the CRSP index (CRSP stands for the Center for Research Security Prices developed at the University of Chicago).

|

CRSP

Index

|

Treasury

Bills

|

Real Return

Pct.

|

Std

Dev.

|

Worst

Return

|

Period

Ending

|

|

100

|

0

|

6.5

|

18.9

|

-39.6

|

Feb-09

|

|

80

|

20

|

5.6

|

15.1

|

-30.9

|

Feb-09

|

|

60

|

40

|

4.5

|

11.4

|

-22.0

|

Nov-78

|

|

40

|

60

|

3.4

|

7.7

|

-17.2

|

Nov-48

|

|

20

|

80

|

2.0

|

4.2

|

-29.4

|

Nov-48

|

|

0

|

100

|

0.6

|

1.8

|

-42.1

|

Feb-51

|

| 1927 - 2010 |

|

|

|

|

|

The annualized columns provide summary risk and return statistics for these portfolios over the 85 years in the study. The inflation adjusted return for Treasury Bills has been 0.60% per year or 60 basis points. The inflation adjusted return for stocks has been 6.48% per year. The standard deviation or the measure of risk has been much greater for stocks (18.86) than for treasury bills (1.81).

There are many different ways to talk about risk. For example, take the worst 10 years for these various portfolio combinations. This is calculated by looking at the 900 or so combinations of 10-year data using monthly returns. Starting with Treasury Bills, the worst real return for Treasury Bills was minus 42%. That was the 10 years ending February 1951. This is of particular interest to us now, because over that time period Treasury Bills returned less than 1% per year while inflation was 6% and we are now back to a situation where Treasury Bills yield below 1%. Turning to stocks, the worst 10 year-period in real return for stocks was minus 39%. That was the 10-years ending February 2009.

It’s not surprising that people are having a lot of concern about stock returns having recently lived through 2007-2009 and February through March 2020. But in terms of real returns the worst 10-year experience of Treasury Bills is poorer than the worst 10-year return on stocks. By this measure, the Treasury Bills are riskier than the stocks. Although it might appear to be riskier to accumulate wealth in stocks rather than in Treasury Bills, over longer periods of time precisely the opposite is true.

So, we have two different conclusions about risk and return, depending on how we measure risk; whether we use volatility or we look at purchasing power. In terms of the worst 10-year experience, the best outcome in this simple example is really for the portfolio that is 40% invested in the stock index and 60% invested in Treasury Bills. This doesn’t prove anything, but it does conform to our conviction that most investors require a 60 -70% allocation to stocks to earn the returns that will allow them to meet their long-term goals and objectives.

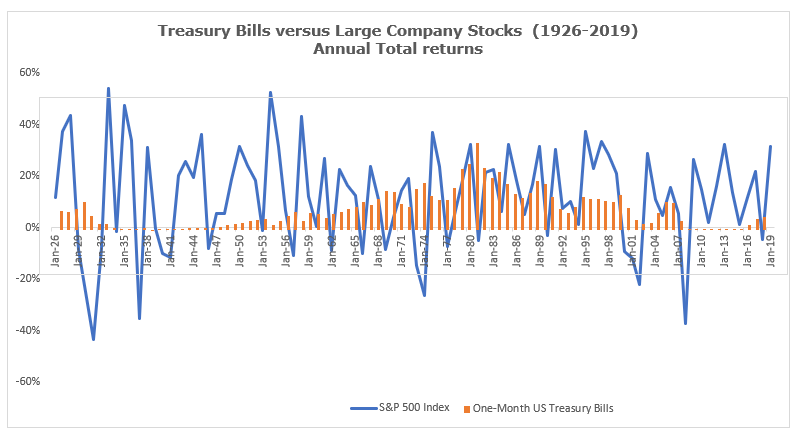

A Model for Determining Broad Portfolio Balance

The following chart contrasts the return volatility characteristics of Treasury Bills vs large company stocks, as measured by the S&P 500 Index from 1926 through 2019. Treasury Bills’ stable pattern of positive annual total returns looks like the skyline of a large city. Superimposed on this is the wildly fluctuating pattern of annual total returns for large company stocks. Over the entire 94-year period, 1981 was the only year when Treasury Bills returned in excess of the 12.09% arithmetic return on large company stocks. This point isn't meant to justify common stock investing for short-time horizons because over one third of the time, large company stock annual returns lagged those of Treasury Bills, often by a significant margin.

It’s easy to identify the particularly bad years for large company stocks. It’s also fairly easy to spot the bad 2 and 3-year periods. It is more difficult to identify bad 5 and 10-year periods, since good years invariably became averaged in with the bad years. The passage of time, therefore, mitigates the risk posed by volatility while providing an opportunity to earn the higher returns from stocks.

The high level of large company stocks volatility is quantifiable by the standard deviation statistic, in this case 19.76%. With the simplifying assumption that stock returns are normally distributed, roughly two thirds of the yearly returns for stocks should fall within plus or minus 19.76% of their 12.09% arithmetic mean.The relative range defined by one standard deviation is 39.52%, wide. Historically the reward for bearing this volatility has been an incremental compound return of 6.4% above that available from stable principal value Treasury Bills. But because the expected reward for bearing the volatility is small relative to the level of volatility, the high volatility of common stock returns will often swamp their short-term expected reward. A corollary of this observation is that short-term common stock performance is meaningless for a truly long-term investor. And time horizon is the key variable in determining the appropriate balance of stocks versus bonds. The following table shows the volatility/return characteristics of five portfolios ranging from 100% Treasury Bills through 50% Treasury Bills/50% large company stocks to 100% invested in large company stocks. In this study large company stocks are measured by the S&P 500 Index.

|

Portfolio Balance

|

|

Modeled Portfolio Performance

|

|

|

T-Bills

|

Large Caps

|

|

Return

|

|

Volatility

|

|

Typical Range of Results

|

|

1

|

100%

|

0%

|

|

3.37%

|

|

± 0.0%

|

|

3.37%

|

|

2

|

70%

|

30%

|

|

5.81%

|

|

± 6.16%

|

|

-0.35% to 11.97%

|

|

3

|

50%

|

50%

|

|

7.64%

|

|

± 9.82%

|

|

-2.18% to 17.46%

|

|

4

|

30%

|

70%

|

|

9.40%

|

|

±13.71%

|

|

-4.31% to 23.11%

|

|

5

|

0%

|

100%

|

|

12.09%

|

|

±19.76%

|

|

-7.67% to 31.85%

|

|

1926 - 2019

|

In reviewing the range of combinations, the portfolio composed entirely of Treasury Bills has the lowest modeled return. As money is allocated to large company stocks, the volatility of the resulting portfolio increases in direct proportion to the percentage invested in stocks. Psychologically, it is easier to tolerate volatility if the final outcome occurs in the distant future. Unfortunately, the liquidity of the capital markets provides constant revision of security prices and a heightened awareness of short-run performance. The trick is to avoid attaching too much significance to short-term performance numbers if the relevant outcome is truly associated with a long-term time horizon.

The tables below show in tabular form the “distributions of portfolio annualized returns”, which describe the likelihood of achieving various returns over 1, 3, 5, 10, 15 and 25-year time horizons for portfolios 1 through 5. Examining the annualized distribution of returns for portfolio 3 (50% stocks and 50% Treasury Bills) shows that negative -4.3% is shown at the 10th percentile for a one-year horizon. This means that there is a 90% likelihood that the actual return will be higher than negative -4.3% and 10% likelihood that the actual return will be lower. Under the 10th percentile column for a 5-year time horizon, we see a value of positive 1.27%. That is, there is a 10% likelihood that for a 5-year holding period, this portfolio will have a compound annual return in excess of 1.27%. For a 15-year horizon there is a 90% likelihood that the compound annual return will be greater than positive 3.95%, —an interesting outcome when one considers that the median return available from Treasury Bills for the same horizon is positive 3.54%. In other words, with a 15-year investment horizon, the chances are 9 out of 10 that a 50/50 mix of Treasury Bills and large company stocks will outperform an all Treasury Bill portfolio.

|

100% Treasury Bills | Portfolio 1

|

|

Yrs

|

1st%

|

10th%

|

25th%

|

50th%

|

75th%

|

90th%

|

99th%

|

|

1

|

-0.01%

|

0.10%

|

0.59%

|

2.89%

|

5.23%

|

7.72%

|

13.47%

|

|

3

|

0.01%

|

0.12%

|

0.68%

|

2.70%

|

5.24%

|

7.20%

|

12.11%

|

|

5

|

0.04%

|

0.15%

|

0.76%

|

2.78%

|

5.35%

|

7.02%

|

11.09%

|

|

10

|

0.14%

|

0.29%

|

1.11%

|

3.09%

|

5.49%

|

8.38%

|

9.15%

|

|

15

|

0.22%

|

0.53%

|

1.25%

|

3.54%

|

5.71%

|

7.94%

|

8.32%

|

|

25

|

0.64%

|

0.90%

|

2.02%

|

3.86%

|

6.51%

|

7.01%

|

7.24%

|

|

30/70 | Portfolio 2

|

|

Yrs

|

1st%

|

10th%

|

25th%

|

50th%

|

75th%

|

90th%

|

99th%

|

|

1

|

-12.88%

|

-1.85%

|

2.47%

|

6.16%

|

10.26%

|

13.34%

|

20.02%

|

|

3

|

-6.40%

|

0.44%

|

3.66%

|

5.61%

|

8.05%

|

11.49%

|

13.78%

|

|

5

|

-1.55%

|

1.72%

|

3.68%

|

5.52%

|

7.65%

|

10.22%

|

13.23%

|

|

10

|

1.25%

|

2.66%

|

3.68%

|

5.61%

|

7.43%

|

9.95%

|

11.76%

|

|

15

|

1.83%

|

3.12%

|

4.04%

|

5.80%

|

7.32%

|

9.75%

|

10.64%

|

|

25

|

3.12%

|

4.47%

|

5.13%

|

5.93%

|

8.03%

|

8.84%

|

9.84%

|

|

50/50 | Portfolio 3

|

|

Yrs

|

1st%

|

10th%

|

25th%

|

50th%

|

75th%

|

90th%

|

99th%

|

|

1

|

-21.82%

|

-4.30%

|

2.04%

|

8.20%

|

14.18%

|

19.38%

|

30.16%

|

|

3

|

-12.36%

|

-0.53%

|

4.92%

|

7.35%

|

11.13%

|

14.15%

|

18.76%

|

|

5

|

-3.94%

|

1.27%

|

4.62%

|

7.18%

|

10.19%

|

12.70%

|

16.35%

|

|

10

|

0.61%

|

3.41%

|

5.03%

|

7.15%

|

9.53%

|

11.77%

|

13.51%

|

|

15

|

2.09%

|

3.95%

|

5.52%

|

7.45%

|

9.15%

|

11.56%

|

12.50%

|

|

25

|

4.34%

|

6.22%

|

6.87%

|

7.66%

|

9.03%

|

10.14%

|

11.73%

|

|

70/30 | Portfolio 4

|

|

Yrs

|

1st%

|

10th%

|

25th%

|

50th%

|

75th%

|

90th%

|

99th%

|

|

1

|

-30.44%

|

-7.51%

|

1.35%

|

10.25%

|

18.28%

|

25.58%

|

42.17%

|

|

3

|

-18.52%

|

-2.14%

|

5.10%

|

9.17%

|

13.59%

|

18.11%

|

24.50%

|

|

5

|

-7.08%

|

0.51%

|

4.92%

|

8.79%

|

12.57%

|

15.40%

|

20.77%

|

|

10

|

-0.43%

|

3.68%

|

5.99%

|

8.37%

|

12.11%

|

13.79%

|

15.32%

|

|

15

|

1.90%

|

4.41%

|

6.34%

|

8.72%

|

11.54%

|

13.11%

|

14.85%

|

|

25

|

5.30%

|

7.42%

|

8.04%

|

9.20%

|

10.34%

|

11.47%

|

13.56%

|

|

100% Large Cap Stocks | Portfolio 5

|

|

Yrs

|

1st%

|

10th%

|

25th%

|

50th%

|

75th%

|

90th%

|

99th%

|

|

1

|

-42.66%

|

-12.62%

|

0.24%

|

13.02%

|

25.09%

|

36.15%

|

59.28%

|

|

3

|

-28.25%

|

-4.80%

|

5.09%

|

11.44%

|

17.25%

|

24.74%

|

34.10%

|

|

5

|

-12.94%

|

-1.18%

|

4.88%

|

10.91%

|

15.85%

|

20.24%

|

26.82%

|

|

10

|

-2.63%

|

3.16%

|

6.96%

|

9.98%

|

15.12%

|

17.37%

|

19.79%

|

|

15

|

0.79%

|

4.79%

|

6.93%

|

10.55%

|

14.53%

|

16.61%

|

18.65%

|

|

25

|

6.17%

|

8.37%

|

9.54%

|

10.71%

|

13.08%

|

14.00%

|

16.17%

|

And per the power of compounding the cumulative wealth from an investment in large company stocks would double that of a corresponding investment in treasury bills in only 11 years. By 17 years large company stocks would be worth about three times the value of an investment in Treasury Bills. As expected with longer time horizons, there are more opportunities for good and bad years to offset each other, thereby narrowing the range of outcomes and the downside risk posed by volatility. The objective here is not to convert "risk avoidance" investors to "risk takers". Rather, the task is to sensitize investors to all types of risk and then to prioritize the relative dangers of those risks given the context of the situation. This is why we explored in detail, in the examples above, the impact that time horizon has on the investment management process. It is only in reference to the relevant time horizon that we can determine whether volatility or inflation is the greater risk. Because risk is time horizon dependant, for the long term investor, inflation not volatility is the major risk.

In summary, volatility swamps the expected payoff from common stocks in the short-run, making them a risk not worth taking. But in the long-run, common stocks emerge as the winner because of the convergence of average returns around common stocks higher expected return, coupled with the miracle of compounding interest. Time horizon is the key variable in determining the appropriate balance of stocks versus bonds in a portfolio. For a long-term time horizon inflation poses a larger risk than the stock market volatility. And accordingly, a portfolio should be oriented more heavily toward common stocks and other forms of equity investments. For a short-term time horizon, stock market volatility is more dangerous than inflation, so portfolios should be more heavily positioned in Treasury bills and other interest-bearing investments that have more predictable returns.

Learn More About Us

Cardiff Park Advisors is located in San Marcos, 25 miles north of San Diego. We work with clients throughout the United States. We welcome the opportunity to discuss your financial goals and how we can help you reach them. You may reach us by emailing our principal at jgorlow@cardiffpark.com or calling our office at 760-635-7526.

For more information about Cardiff Park Advisors please review our brochure at https://adviserinfo.sec.gov/firm/summary/126752 or visit www.cardiffpark.com